|

|

|

Veracruz

Visiting the Witches of Veracruz

by David Lida

May/Mayo 2000

My first witch is a man of medium height, with sleek black hair combed back from his forehead, and skin the color of coffee with cream. He wears a sky-blue polyester shirt and three gleaming gold chains across his chest. He also wears several gold rings and reveals gold-capped front teeth as he speaks. His eyes are as black as ravens' wings; his piercing gaze penetrates to the point of intimidation.

His name is Tito Gueixpal Seba. "I am a specialist in black magic," he tells me. "All illness, all accidents, all bad luck and even death are caused by la maldad negra - the black evil. I can take away the black evil by bringing in la poder blanca - the white power - to overtake it. With white prayer, I can unearth what has been buried in the graveyard by black prayer; the white cures the black."

The walls in his workroom are painted black. Dozens of striped candles, and plastic bottles filled with liquids of different colors - red, green, yellow, blue - lead in tiers up to an altar to the Virgin of El Carmen. Amulets for luck line his desk. They depict St. Martin on horseback.

He produces an object wrapped in brown-stained newspaper. "I can also bring about the black evil, and cause great harm, even death," he says, his eyes more alarming than ever. "All I need is someone's name, their photograph and a piece of their clothing." He unwraps the package and shows me a doll formed from what looks like parachute silk, dyed brown and tied in place with black thread.

"Is that stained with coffee?" I ask.

"Touch it," he says. It is sticky, gluey. "That's not coffee. It's the oil of the dead."

I'm in Los Tuxtlas, in southern Veracruz on the Gulf Coast of Mexico. A region comprised of three towns - San Andres Tuxtla, Santiago Tuxtla and Catemaco - Los Tuxtlas is famous for various reasons. Mexico's oldest civilization, the Olmec, flourished here between 900 and 600 B.C. Formerly rain forest, Los Tuxtlas is one of the country's most fertile territories; on the road you see and even smell mango, papaya, pineapple, melon. It's also tobacco country, where internationally well-regarded cigars are produced. Fish and seafood proliferate in its rivers; fat cattle graze on its lush ranches.

This is deep Mexico, Mexico for aficionados: Although filled with warm and friendly people, in Los Tuxtlas, you have to do a little work to find a bank, a newspaper, a hotel with an efficient air conditioner or people who speak English. The weather is intense: acute heat and humidity, frequent rain.

Yet Los Tuxtlas has a special attraction. Above all, it's famous for brujeria - witch-craft. All over Mexico I have heard people talk about the witches here - the curanderos who cure illnesses with plants and herbs and oils, and the brujos who cause spells, good and bad. Some set broken bones, some act as magical midwives while women give birth. Others read kernels of corn like tea leaves. Still others are reputed to bring back straying husbands, help save failing businesses, cause fatal damage to enemies.

Many Mexicans give credence to witchcraft. In every market in the country, there is at least one stall selling scented candles, mysterious oils and herbs, as well as boxes of soaps and packets of powders that promise, in words or pictures, good luck, success, protection for the home or new hair growth. (My favorite, depicting a woman with a gag over her mouth is called jabon de callarme - soap to shut me up.) Yet the witches of Los Tuxtlas have emerged as something of a tourist attraction. Few foreigners come here, but Mexican vacationers are lured from all over the repubic.

When I visited Los Tuxtlas recently, I was determined to find out as much as I could about the witches. I was skeptical, but uneasy about the task. In his book A War of Witches, about brujeria in another region of Mexico, anthropologist Timothy J. Knab depicts people who kill and maim through the use of toxic herbs, poisonous bat droppings, or the slashing of the jugular vein with extracted jaguar's teeth.

Dr. Jeffrey Wilkerson, who heads the Institute for Cultural Anthropology of the Tropics in northern Veracruz, looks upon the area's witches with great skepticism. He explains that Los Tuxtlas was "high jungle" until the 1940s, when good roads were finally extended and the region was fully cultivated. Until then doctors and hospitals were scarce, and given the area's nature, there was a strong and longstanding tradition of healers who lived in the jungle and learned the medicinal properties of plants, herbs and even animals.

"People all over the south along the Gulf Coast sent their ill to Los Tuxtlas for the best curanderos," says Wilkerson. But he adds that, unlike traditional curanderos, the brujos of today are simply "a gimmick with a historical root, promoted by people with tourist interests, like hotel owners. It's publicity, promotion, a modern creation."

Dissenting, Fernando Bustamante doesn't draw such a fine distinction between curanderos and brujos. Bustamante, the director of the Museo Tuxteco in Santiago Tuxtla, which houses some of the Olmec treasures found at the nearby Tres Zapotes archaeological site, feels that they are of the same species.

"When the curanderos began to say that they could cause 'spells,' that they could resolve problems or cause harm, this added an element of psychotherapy to their practice," explains Bustamante, a gray-haired raconteur who has raised children and grandchildren in Santiago Tuxtla. "If I like a girl, but I'm too shy to approach her, and a brujo gives me an amulet that contains powder, perfume and a rock, when I see the girl, I grab the amulet and suddenly feel power surging through me. Then I approach the girl and the language of pheromones starts talking." He laughs, shrugging. "It's a lot cheaper than going to a psychiatrist."

Bustamante notes that uninitiated tourists in the region are frequently the object of scams by the witches, but offers to introduce me to three of them who are his friends. The first is the sinister-looking Tito Gueixpal. Almost immediately, Gueixpal warns me that I suffer from envidias - envy. Well, sure, I think, remembering various journalists whose bylines I see more frequently than mine.

This is the wrong interpretation. Gueixpal explains that there are people out there envious of me, who in their maldad are keeping me from the professional success I justly deserve. He offers me a limpia - a cleansing to expunge these forces.

Seating me in a chair, Gueixpal has me repeat after him a prayer in Spanish asking the lord to take away harm, to save me from the enchanted snakes buried in the graveyard of evil, to give me salvation from the professional jealousies. As we incant, he grabs a bottle of brackish green liquid that he says contains basil, rosemary and rue (and which smells like alcohol), and splashes it all over not just the exposed parts of my body - my arms, neck and head - but my clothes as well. He fills his mouth with a blue liquid and spits it all over me, several times over. The limpia is finished in minutes. "You're cured," says Gueixpal, handing me an amulet for good luck and a fat stack of business cards to distribute among my acquaintances. I feel entirely magnetic for ten minutes after our meeting - I don't know whether from his powers, or being drenched in herbs and alcohol, or the shock of a stranger spitting something blue atop my glistening bald head. Whether "real" or not, Gueixpal has done very well as a witch - he lives in a big house in downtown Catemaco with his wife and children.

My second witch, Gilberto Rodriguez Pereyra - also known as El Diabolico - has an even larger house in San Andres Tuxtla. His business card assures that he can cure "sentimental problems," bad luck in business, envies and jinxes (as well as pointing out that he's been interviewed by a prominent Latin-American TV star). Rodriguez is a slender man with a placid, sober expression, conspicuously red hair and lots of jewelry - silver rings depicting an owl, a skull and a serpent; gold, amber, red, black and jade necklaces, the last of which contains the spiked teeth of an animal he declines to name.

"People come to me who have had no luck with doctors," he says. "I have cured cancer. I have cured people who couldn't walk. I cured a man who had been bewitched; he couldn't speak and had his tongue hanging out. It was enormous, like a dog's tongue. I evoked God and the Great Lord of the Fog - Lucifer. I asked him to obey my orders and come into the light. Satan obeys the light."

Like Gueixpal, Rodriguez claims to be able to cause great harm to a person - with nothing more than their name. I ask him if he has any pangs of conscience when casting a spell on someone who may be innocent. He raises an eyebrow. "If someone pays me," he says, "I have to perform. If I don't, they say I'm a liar, that I have no powers."

Inside the thatched-roof hut in Rodriguez's backyard where he performs his magic is a collage of photos of him with various VIPs - the governor of Veracruz, former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, a Brazilian soap-opera star and a stunning vedette in a bikini. When I mention that I have certain mild respiratory problems, he recommends that I make a tea with seven leaves of sweet basil and a red rose, and to drink it when it cools.

Our interview is cut short, however, when two clients - expensively dressed, dyed-haired matronly senoras - arrive. Rodriguez gives me an amulet for good luck before I leave.

My third witch, unlike the first two, has clearly reaped no great financial gains from her occupation. Dona Julia Gracia lives in a two-room shack with a dirt floor, cardboard walls and a corrugated tin roof in the humblest neighborhood in Santiago Tuxtla.

She is diminutive, hunched and wears a common housedress covered with an apron. She claims to be 64, but the cross-hatched wrinkles around her eyes, forehead and cheeks, and her absence of all but one front tooth, seem to bely her mathematical prowess.

She speaks in a whisper. She defines her work as "to take away the bad and replace it with the good." Dona Julia says that people have come from "all over the world" to see her, and to illustrate, names a dozen indigent towns in southern Veracruz.

She says she can cure espantos (sort of cosmic frights), "airs in the head," and romantic problems. She shows me three dolls, each formed from melted candle wax. They have human hair attached with pins, and ribbons of different colors. One, she says, is to bring back a straying spouse, another to attract an indifferent lover. The third is para alejar - to banish the extramarital lover far from the cheater's life.

Our chat is interrupted by a customer - a girl of about 15 is suffering from intestinal problems (unfortunately a chronic complaint in impoverished parts of Mexico, mostly due to poor sewage systems and drinking unfiltered water). Before her altar to the Virgin of Carmen, decorated with white candles and strewn with white lilies, Julia gives the girl a limpia. In her prayer, she evokes various Catholic saints, including Peter, Martin and Mary. She splashes the girl with blanquillo - a clear liquid - and rubs an egg over her forehead, arms, neck and legs. She also passes a soaked bundle of herbs - again basil, rosemary and rue, the holy trinity of Mexican witches - over the girl's body and under her shirt.

When she finishes, she cracks the egg into a glass and shows the girl that the albumen is filmy, milky, murky. This, explains Julia, is the maldad the girl was suffering from, which she was able to extract. Now, announces Julia, the girl is cured. She charges five pesos - less than a dollar at the current exchange rate.

Visiting the modest world of Dona Julia makes me ponder whether I'm missing the point by wondering if Mexican witchcraft is "real" or not. An attempt to answer that question only evokes further questions: How can we define "real"? Are the practices of Mexican witches so different from modern medicine in the United States, where a witch in a white coat with a stethoscope around his neck gives us a pill to cure us of our ailments? How much of our being healed depends on our faith, on our belief in him? Even in the U.S. there is a growing movement of homeopathic, herbal and natural medicine, as evidenced by the popularity of such practitioners as Andrew Weil. Not to mention our beliefs in other arcane products and practices: Rogaine, Fen Shen, daily horoscopes, the Psychic Friends Network.

And here in Mexico, how much of "witchcraft" is a consequence of the uneasy marriage between Catholic faith and indigenous belief? All three witches I visited evoked Catholic saints and prayers.

In any case, in this sweaty, obscenely fertile, jungly region of southern Mexico, off the established tourist trail, where ills were cured with herbs and plants long before the Spanish conquerers arrived, it's hard not to believe, hard not to be bewitched.

Looking into the limpid eyes of Dona Julia, I am moved by her caring, maternal nature, her essential sweetness. I recall another wry comment of Fernando Bustamante: "We've all had the experience as children of having a headache, and feeling better when our mother puts her hand on our forehead." In this sense, he posits that "all mothers are witches."

If it's hard to tell what's "real" among the witches, one thing is certain - they're here to stay. Several of Dona Julia's grandchildren ran in and out of her shack during my visit. The youngest, Julieta, about three years old, seemed to be the apple of the old woman's eye. At one point she hugged the child to her breast and laughed. "When she grows up, she's going to be a witch, too," she said.

|

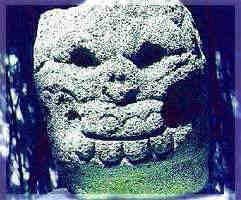

Olmec skull

Olmec skull

|

|

|

|

Visiting the (witch) doctor

By MANNY GONZALES

Nov. 12, 2000

CATEMACO, Mexico -- Blank faces of the cursed and smiling faces of the blessed stared at me through black soot from photos on the walls of witch doctor Tito Guenpal Seba's office.

The smell of incense mingled with cheap cologne among dozens of candles burning beside paintings of Jesus Christ. Wood carvings of a baboon and a lizard sat at the feet of a statue of the Virgin Mary.

Here, in this well-kept house (though modest by our standards), Catholicism clashed with ancient magical forces passed from generation to generation for 3,000 years.

It was partly to sample such a phenomenon that I had come to Veracruz, a skinny state averaging 55 miles in width that stretches, crescent-shaped, for 430 miles along the southwest side of the Gulf of Mexico.

Unlike the Mexican coastal resorts such as Cancun, Veracruz still offers visitors a flavor of old-world traditions.

I relied on locals such as Spokane, Wash., transplant Roy Dudley of nearby Jalapa and English-speaking tour guide Temoc Benitez to take me off the beaten path.

Catemaco is a rural community of about 20,000 beside a peaceful lake in southern Veracruz state. It's ringed by low, rolling mountains and plantations of fruit, coffee beans and tobacco, plus a tropical rain forest.

Founded in 1667, the area is known for its orchids and nearly 400 species of birds. Visitors ride flimsy wooden boats on tours of the placid lake.

While witchcraft has had a home here since the Olmecs (Mesoamerica's oldest civilization) ruled the land 3,000 years ago, recent years have sparked new interest.

Today, Catemaco is known as the City of Witches. Tourism officials promote the local occult, especially the "Annual Convention of Wizards" on the first Friday of March, when thousands of visitors pay to to be rid of evil spirits or plain bad luck. Tourists stroll the streets looking for someone to lead them to a witch doctor.

It was easy even for a visitor to see that witchcraft has influenced the local business community.

Many businesses use the word brujo (meaning witch) in their names. There is the wooden-hut restaurant called Seven Brujos and the Brujo Inn. There is even a Brujo coffee house.

A police officer pointed us toward Guenpal Seba's home, along a dirt road just south of town. The stucco house looked like a castle compared to the many shanties in the neighborhood.

The outside wall had a 5-foot-tall painting of a Bengal tiger. A sign beneath it warned that we were entering the lair of a black-magic brujo.

The place reminded me that in the tiny, predominantly Mexican-American enclave where I was raised in southern Colorado, neighbors told tales of curanderos (curers) or brujos who practiced magic passed down from ancient Indian tribes of South America and southern and central Mexico.

I never really believed in witches. But stepping into Seba's office made me rethink.

His jet-black hair was slicked back over his leathery-skinned face. His silver-haired mother, who greeted us when we walked in, sat by the door to keep other customers from interrupting.

Seba would "cleanse" my spirit or cast a curse for about 500 pesos, a little less than . A charred voodoo doll was at his side -- a sign he meant business. Photos of himself doing a "spiritual cleansing" of former Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo were on the wall.

"If the president comes to this guy, this place has to be the real thing," Benitez said.

When Seba wanted 500 pesos to cleanse me of evil spirits, Benitez, who was interpreting, began bargaining. It made me a bit nervous. After all, it was my soul on the table here.

In broken English, Seba countered with an offer of a speedy spiritual cleansing -- and good luck -- for 200 pesos (a little less than ).

I sat facing the wall of blackened photos. Benitez stood beside me. Guenpal Seba sat in a chair in the opposite end of the room as his young apprentice spread oil that smelled strongly of alcohol, first over my arms, then my legs. He then took a mouthful and spat it in my face. The oil would clean me of spirits, Benitez said.

Seba's chants in Spanish and in some sort of Indian language were foreign even to Benitez.

There is white magic and black magic, Guenpal Seba explained to Benitez in Spanish. Black magic, he said, is the most powerful, but there are often consequences for dealing with dark forces.

"I can change my shape into any animal I wish, but doing so would mean giving my family's souls to the devil," he said.

The session over, we walked into the bright sun. I reeked of alcohol. My arms and neck tingled as fresh air hit my skin. Benitez suggested the tingling might be the magic at work. I told him it was the alcohol in the oil.

Whichever it was, I knew I had taken part in a tradition thousands of years old.

Witchcraft link

WITCHCRAFT & SORCERY IN MEXICO

by Ralph F. Graves

She used to hold court at the rear table of a small outdoor cafe in Acapulco´s "old town." At first, I thought she was the owner; but no, Maria was much more important. She was a curandera, or curer. She consulted throughout the day with various clients; reading fortunes with a set of tattered tarot cards, offering advice on love, money and family affairs; and dispensing information on herbal cures and "cleansing" potions.

"My mission in life is to help people," she told me after reading my palm. "But I am not a bruja (witch) as some people think." Pressed further, she explained, "The true witch or warlock can cast spells . . . or cure them, They are born with special powers for good or evil."

Witches, warlocks, shamans, curers, sorcerers, or whatever they may be called, the practitioners of magic-both white and black are revered and sometimes feared in Mexico.

For this is a country where belief in the occult proliferates not only among the rural and uneducated segments of society, but permeates the upper classes as well.

In the late 1970s, for instance, the niece of then President Lopez Portillo announced via national news media that her "problems" had been cured after consultations with a famous warlock. In fact, many affluent men seek advice from shamans about their business, their family or perhaps, their mistress.

Young women want to better their love life. And others, in all walks of life, seek consultations out of fear, curiosity, envy, greed or some other perceived need.

Of course, belief in witchcraft is as old as mankind, and in Mexico, its roots lie in both Hispanic and pre-Hispanic cultures. The use of herbs and potions were parts of elaborate rites and ceremonies to cleanse or purge evil spirits in ancient America. And the Spanish conquerors imported their medieval superstitions and beliefs that had roots in the Dark Ages of Europe; indeed, it is unclear whether today´s rituals of "cleansing" originated with the conquerors or the conquered.

But they have survived the advances of modern medicine and are often used as a last resort when the latest drugs or surgical procedures have failed to produce the desired results. Cleansing, or purification, is often sought because a person (or in some cases, a house or business establishment) is believed to be suffering from a negative aura, curse or an evil spell. In mild cases, a curer or shaman may prescribe magical amulets, charms or potions that are easily available in the market place. A dried hummingbird might be prescribed as a man´s love charm; a goat´s beard is to be burned and the smoke inhaled to cure certain internal maladies; laurel is often used as a cleansing agent and deer´s eye seeds can be worn as an amulet to repel the effects of an "evil" eye.

For more serious cases, a patient is likely to be referred to a witch or warlock for a formal cleansing ritual. These are usually performed by "white" or good witches, since the problem was apt to be the work of a "black" or bad witch. The specific technique will vary by the practitioner, but some of the more common cleansing elements are eggs, frogs, hens and herbs or other magical plants.

In a typical cleansing rite, the practitioner will have the patient lie in front of an altar of colored candles and branches. An examination is made to determine the source of the problem. Incantations and supplications are made to the spirits and the cleansing agent is passed over the patient´s body to draw out the evil and transfer it to the agent. An appropriate potion is administered and the agent destroyed.

For all the conjuration and ritual, however, the patient´s belief in the curative process seems to be the determining factor in its success.

So prevalent is witchcraft in Mexico, its practitioners have their own national convention. Held each March in the tiny town of Catemaco, Veracruz, it draws witches, warlocks, curers, shamans, psychics, parapsychologists, wizards and sorcerers from all over the country. It is believed the site and the date for this event go back to the ancient Olmecs and is based on the annual ceremonies that purified their temples.

At any rate, this is an occasion that calls for communing with the spirits and receiving new revelations from them. It is also a time of ritual initiation of new witches and warlocks. During the night, two important rituals are performed.

One is of white magic, where rings of plants and flowers surround incense, lotions and purified water. A black magic ritual features symbols of demons, snakes, bats, owls, etc. surrounded by a ring of sulphur. Many of the conventioneers have great fame and acclaim among those who believe in and practice witchcraft. As widespread as the practice is in Mexico, one might never suspect that witchcraft is illegal here. But, according to the third article of the Mexican Constitution, this type of "Charlatanism" is prohibited.

But try explaining that to Maria. "Where else can people go to get help with their problems?" she asks. "A doctor can treat a broken leg, but who except a curer can treat a broken heart?"

Witchcraft link

|

Witch

Witch

|

Salem witchcraft 1692

A small girl fell sick in 1692. Her convulsions, contortions, and outbursts of gibberish” baffled everyone. Other girls soon manifested the same symptoms. Their doctor could suggest but one cause. Witchcraft.

That grim diagnosis launched a Puritan inquisition that took 25 lives, filled prisons with innocent people, and frayed the soul of a Massachusetts community called Salem.

Be sober, be vigilant; because your adversary the devil,

as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour.

1 Peter 5:8

Zealously obedient to this admonishment from the apostle Peter, the Puritans of New England scoured their souls”and those of their neighbors”for even the faintest stains. These stern, godly folk were ready to stare down that roaring lion till Judgment Day saw him vanquished.

But while the good people of Salem had their eyes on eternity, the lion walked softly among them during the 1670s and 1680s. Salem was divided into a prosperous town”second only to Boston”and a farming village. The two bickered again and again. The villagers, in turn, were split into factions that fiercely debated whether to seek ecclesiastical and political independence from the town.

In 1689 the villagers won the right to establish their own church and chose the Reverend Samuel Parris, a former merchant, as their minister. His rigid ways and seemingly boundless demands for compensation”including personal title to the village parsonage”increased the friction. Many villagers vowed to drive Parris out, and they stopped contributing to his salary in October 1691.

Seeking release from the tension choking their family, Parris nine-year-old daughter, Betty, and her cousin Abigail Williams delighted in the mesmerizing tales spun by Tituba, a slave from Barbados. The girls invited several friends to share this delicious, forbidden diversion. Tituba audience listened intently as she talked of telling the future.

The lion roared in February 1692. Betty Parris began having a fitt that defied all explanation. So did Abigail Williams and the girls friend Ann Putnam. Doctors and ministers watched in horror as the girls contorted themselves, cowered under chairs, and shouted nonsense. The girls agonies could not possibly be Dissembled, and declared the Reverend Cotton Mather, one of the brightest stars in the Massachusetts firmament.

Lacking a natural explanation, the Puritans turned to the supernatural the girls were bewitched. Prodded by Parris and others, they named their tormentors: a disheveled beggar named Sarah Good, the elderly Sarah Osburn, and Tituba herself. Each woman was something of a misfit. Osburn claimed innocence. Good did likewise but fingered Osburn. Tituba, recollection refreshed by Parris lash, confessed and then some.

The devil came to me and bid me serve him, she reported in March 1692. Villagers sat spellbound as Tituba spoke of black dogs, red cats, yellow birds, and a white-haired man who bade her sign the devil book. There were several undiscovered witches, she said, and they yearned to destroy the Puritans. Finding witches became a crusade not only for Salem but all Massachusetts. Before long the crusade turned into a convulsion, and the witch-hunters ultimately proved far more deadly than their prey.A time to kill, and a time to heal;

a time to break down, and a time to build up.

Ecclesiastes 3:3

Salems time to kill all the more tragic for its theological roots claimed 25 lives. Nineteen witches were hanged at Gallows Hill in 1692, and one defendant, Giles Cory, was tortured to death for refusing to enter a plea at his trial. Five others, including an infant, died in prison.

Each of the four rounds of executions deepened the dismay of many of the New Englanders who watched the witchcraft hysteria run its course. On October 3, 1692, the Reverend Increase Mather, president of Harvard College, denounced the use of so-called spectral evidence. It were better, Mather admonished his fellow ministers (including his son Cotton), that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person should be condemned.

Gov. William Phips grew disgusted when his own wife was mentioned by the afflicted girls. Determined at last to quell the madness, he suspended the special Court of Oyer and Terminer he had earlier established to hear witchcraft cases. He replaced it with a new Superior Court of Judicature which disallowed spectral evidence. That court condemned only 3 of 56 defendants. Phips pardoned them along with five others awaiting execution.

In May 1693 Phips pardoned all those who were still in prison on witchcraft charges. They were free provided they could pay their jail bills.

The time to heal fell under the gentle hand of the Reverend Joseph Green, who in 1697 succeeded Samuel Parris as minister in Salem Village. Green reshuffled his congregations traditional seating plan, placing foes beside one another. As he had hoped, proximity bred charity. At Greens urging, Ann Putnam, one of the leading accusers, offered a public apology in 1706.

Massachusetts as a whole repented the Salem witch-hunt in stages. The colony observed a day of atonement in 1697. It prompted one of the judges to seek public forgiveness for his role in the trials. In 1711 the legislature passed a bill restoring the rights and good names of some of the victims of those dark and severe Prosecutions, awarding restitution to their heirs. Massachusetts apologized again in 1957, and the city of Salem and the town of Danvers (originally Salem Village) dedicated memorials to the slain witches in 1992.

The events presented in this feature were all real, as were the quotations (edited for clarity). The narrative you followed wove different stories together.

|

|

|